One word is enough for me

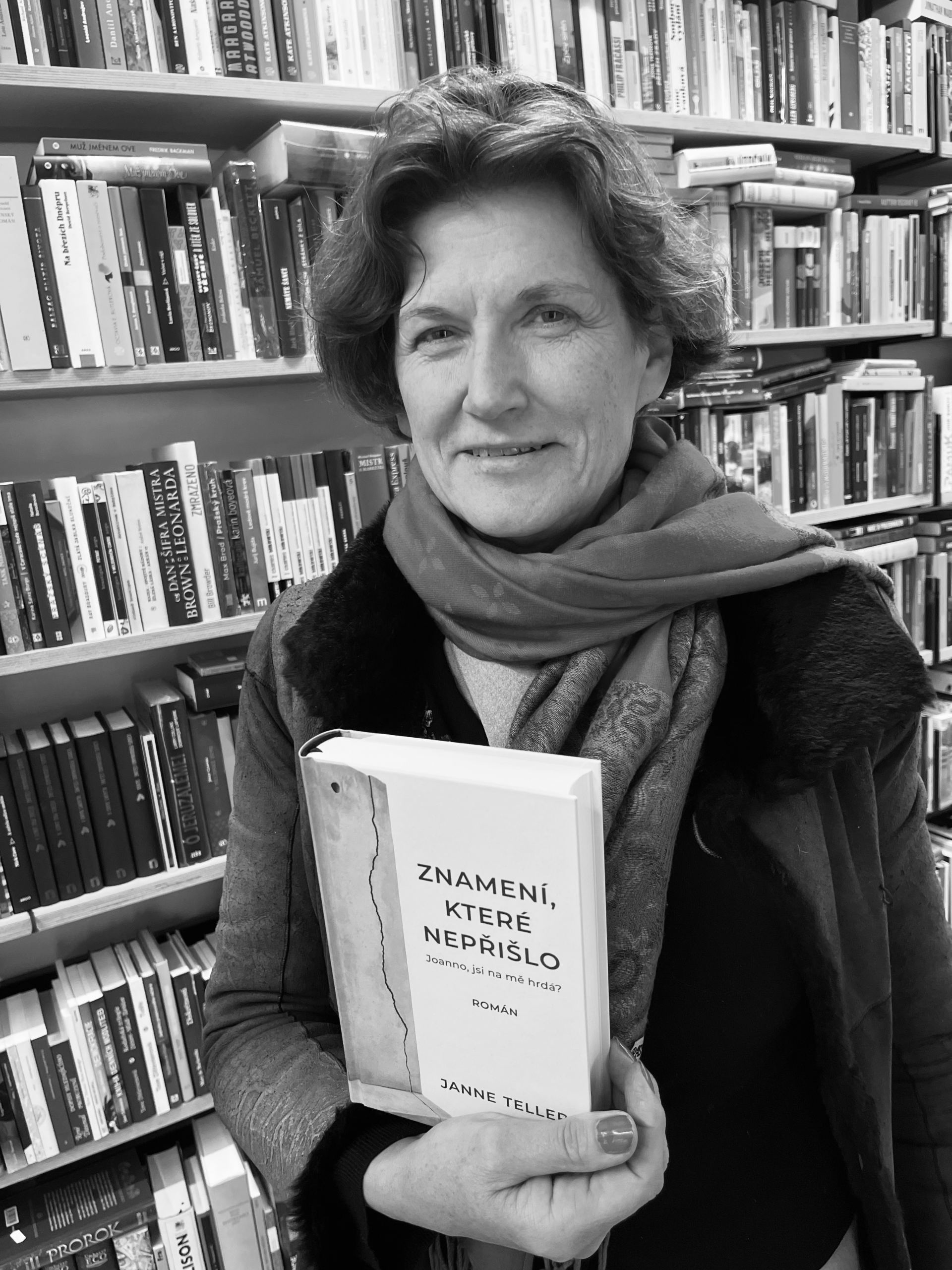

Interview with Danish writer Janne Teller

You recently received an award from the mayor of Budapest. Can you tell me what it was about?

The award is called the Budapest Grand Prize and is given by the Hungarian Publishers & Booksellers Association to an international renowned literary author, who has contributed with outstanding works to world literature, and who has had an impact on the public debate in Hungary. The award was handed to me by the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, who also gave a speech. I should add that Karácsony is independent, and in opposition to Orbán.

I felt particularly honored, because the award had previously been given to authors I greatly admire, such as Günter Grass, Salman Rushdie, Mario Vargas Llosa, Umberto Eco, Amos Oz, Orhan Pamuk, Jonathan Franzen, Daniel Kehlmann, Svetlana Alexievich, … So it is a list that I am very proud to be part of, there are also many Nobel Prize winners among them…

So the Nobel Prize will be next…

Ha ha ha, thank you.

Can you tell me something about yourself, when did you start writing books?

I have been writing since childhood. I think that when you make up stories, you are like a god in your own universe. I had a very chaotic childhood, so for me fiction – being in my own world – meant being in a safe place.

I published my first story in a Danish newspaper when I was fourteen. But because I come from an immigrant family and my parents had no education – my mother is from Austria, she was a child of war coming to Denmark with the Red Cross – it was important to them that I get an education so that I could earn my own living and be financially secure. My parents always told me that in Denmark no one could make a living writing fiction, so I studied macroeconomics as I was also very interested in the world. I worked internationally for the EU and UN, mainly with humanitarian and peace keeping efforts, and spent a number of years in Africa, especially Tanzania and Mozambique.

Did you write in Africa?

I tried to write. But the job was so demanding that I didn’t have much time left to write. So I wrote at night, and it never quite became the level of quality that I wanted. There just weren’t enough hours. On the other hand, thanks to that work, I managed to pay off my student loans, and I saved up some of my last earnings. When in 1995 I returned to Denmark, I rented a small studio apartment and then started writing full-time.

Your imaginary world as a child… what inspired you?

I think I have a very vivid imagination, so it was anything that caught my interest. I liked to invent worlds that were more interesting to me than the one I lived in, even if they didn’t have to be directly inspired by anything. I was always very interested in horses, so initially I wrote a lot about horses. But it could be anything that I perceived, saw, heard, or experienced as a child… And of course everything that I have read and am reading, whether small or large, is also part of the outset for my imagination. But really, say a word, any word, and I can invent you a story about that one word …

Did you have a lot of books at home or did you borrow them? Who was – is your favorite author?

I borrowed books from libraries. As a reader and author, you have the best teachers you could wish for – you can take the works of the greatest writers from all over the world, from any historical period, and they become your personal teachers. My very favorite authors that I learned from were Albert Camus and Knut Hamsun, because what I really love is when you can create a short, simple and poetic story, but with many philosophical layers. The long stories of Tolstoy are interesting, but I prefer the more compact, tighter, denser stories that go deep below the surface.

When I was little, I liked adventure books about Indians, Masai, mammoth hunters, Inuit, or medieval chronicles – all outside the space and time of the communist regime that I hated from a young age. Have you had any similar experiences with inspiration from various indigenous cultures as a defiance against the society in which you grew up?

I think we had it easier in Western Europe at the time. But I much enjoyed the wild nature books of Jack London etc. And yes, it is true that the more I moved in the fantasy and world of literature, the more clearly I saw my own culture – for better or for worse. My first novel, Odin’s Island, was inspired by the magical realism of Latin American authors, which, by being transplanted into the Nordic world and its culture and ancient pantheon, became to a large extent a criticism of, one might say, modern Danish society.

Can you say anything more about that?

In 1999, Odin, the supreme god of Norse mythology, reappears in Denmark. He arrives on an island between Denmark and Sweden, which is uninhabited because it is surrounded by rocks… The Öresund strait between Denmark and Sweden then freezes over, he sets off on foot to Denmark, and a lot of different fanatical groups start thinking that he is their god, and Denmark and Sweden start fighting over the island, which no one has claimed yet because it just looked like a string of rocks.

Odin has lost his ravens, one of which represents clarity of thought and the other represents memory, so Odin doesn’t know who he is or what is going on. Everyone thinks he is an old man who has gotten lost, no one listens to him, neither any of the groups that claim his as their God, but not even the people who are trying to help him. Odin is thus a story about fanaticism, both religious, political and personal …

An interview with the Romanian author Vlad Zografi was recently published in Babylon, who wrote a story about the devil who comes to Romania, but there is no one to seduce, so he starts preaching about morality.

That may be in the same vein of using magic realism to talk about our present world …

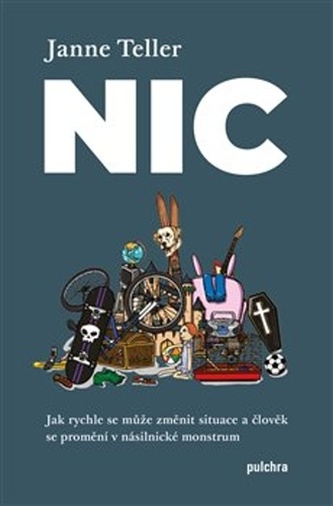

Your book Nothing caused a lot of controversy. How did you come up with the idea and why did the book cause such a stir?

Basically, I put the question of the meaning of life into this book. I never thought I would write a book for teenagers. But my driving force when writing is always trying to somehow grasp things that I don’t understand myself. I thought I couldn’t possibly learn from seeing into the minds of teenagers. But then the story came to me through the voice of the main character, the 14 year old Pierre Anthon, who says: “Nothing matters. I’ve known that for a long time. So it’s not worth doing anything. I just realized that.” Those were the first four lines of the book. And I imagined the boy leaving his class, and sitting in a tree nearby the school, saying these very demoralizing things to his classmates. Like ‘The world is 4.6 billion years old, and you live maximum to 100. Life isn’t worth the bother.’ And I wondered how his classmates would react, and then I realized I had to write that novel.

So nothing matters?

Everything matters, but writing the book helped me understand that, and how to define nothing. The children, in response to their classmate’s pessimism, try to collect “meaningful things” in an old saw mill. The pile becomes increasingly macabre when the severed head of a dog and the coffin of a dead little brother is placed on it, along with a Danish flag and boxing gloves, and next to Jesus on the cross that a religious boy steals from the church. A huge scandal breaks out. In the end, an American museum buys the pile of meaning, claiming it’s modern art, and then the question arises that if we can sell the meaning, then of course you haven’t found meaning? And they need to start looking for meaning again. I myself, when I was writing that book, realized that I didn’t really know how to contradict Pierre Anthon when he says things like: ‘Everything begins only to end. The moment you were born you began dying.’

Because Pierre Anthon is right in the large perspective. But the thing is, we don’t live in the large perspective, we live in the perspective of the here and now. In my opinion, therefore, everything has meaning, even just the taste of what we drink and eat, simply everything that we can experience in life. Thanks to Nothing, I realized to my surprise that although we don’t know anything except that we are here, that we don’t know if God or the Big Bang exists, all possible and impossible theories, but that’s exactly why life is all the more fantastic. It is a gift that someone gave us. We don’t know who, we don’t know why, but we know we have it.

The Pile of Meaning is actually like a metaphor. We use things, the world around us, to affirm ourselves. Instead of freeing ourselves with their help, we close ourselves in on ourselves, we enslave ourselves…

Yes, that’s exactly what I mean. The meaning of our life is not found in the things, nor in the eyes of others. The book Nothing is also a critique of this culture of fame, the goal of which is to try to get other people to look at you. What makes sense, however, is not the way other people see you, but what you see, what you experience, what you feel, perceive. Once we manage to turn this around, our perception of life will change.

My mother was afflicted with senile dementia a few years before her death, or rather she was gifted with it. I have never seen a person who would look at the world around him, trees, houses, birds, dogs, children… with such unfeigned interest, amazement, joy as she did, free from all the morons that we spend our whole lives obscuring our brains with. What are your experiences with African society? What did it give you?

I love Africa. I was in Tanzania for two years and in Mozambique for two years and then I worked for a shorter while in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe and other countries, and this experience changed my view of the world and life as such.

The main thing that struck me right from the start, in Tanzania, was that human relationships are prioritized beyond anything else. Particularly before anything abstract like finishing a report at work or sending a letter, for example, that we Westerners will prioritize. Human interactions, going to family events, funerals, weddings, births take precedence over getting involved in a theoretical project. Coming from northern Protestant Europe with its cult of work, it drove me crazy at first, until I realized that they were actually right.

And I think part of these experiences were also the background for my book Nothing, which questions our Western values and our way of living. Even though there is nothing directly about Africa, the book is certainly inspired by my encounters with African cultures and values.

Were you there alone?

Yes, I went alone to Africa while working for the UN. In Mozambique, due to the war and the risks involved, it was a no-family posting, meaning you could only go as a staff-member on your own. But even in Tanzania, it was quite dangerous at the time 1988-90. We were not allowed to drive alone after dark, but when you live alone, you do it anyway, otherwise you couldn’t go out in the evening. But it also meant I was assaulted a few times, and held up at gunpoint in Dar-es-Salaam and my car was stolen.

You said that Africans prefer human interaction to work – that is basically a very aristocratic view of life …

Yes, when you say it like that, but it’s not how I mean it. When working the land, in the fields where they grow the crops necessary for life, of course they work harder than anyone. It is the abstract kind of work, that will seem senseless, when you have real problems to deal with, like no water, or a sick child and no medicine, a flooded house etc., or even just important family events to help out at or join, then the prioritization of abstract work seems bizarre. And yes – unlike the Africans, we in Europe are slaves to exactly that kind of abstract work.

The novel Kom is about ethics in art… What is the relationship between ethics and art?

The book caused a lot of misunderstanding, because a lot of writers didn’t like that I was raising the question of ethics in our field. The story is about a publisher of a major house who is deciding whether to publish a thriller by a bestselling author – a terrifying story about a gruesome experience in East-Africa of a real-life woman, who is also a writer. She wants the story kept a secret, and ends with the simple words to the publisher: ‘It’s your decision.’ He knows that If he doesn’t publish it, the publishing house loses money, and someone else will anyhow publish the book, and he also reminds himself that the history of literature is littered with examples of great literature written on the private experiences of real people. Yet, something happens in him as a human being when the victim is right in front of him. Thus, the book is a reflection not just on how to deal with ethics in art, but much more on how we can make ethical decisions in this modern competition-driven capitalist society. And the struggle between ethics and profitability, between compassion and self-interests.

Inspired by the conclusion of Albert Camus’s novel ‘The Fall’ that we are all amoral, I take up the natural next question: to which extent we can choose how morally fallen we want to be? And also, I look at how much it will cost us, in our souls or in the comfort of our lives, if we choose one option or the other. It’s a lot about social conventions on the one hand and our humanity on the other. As individuals we may feel powerless, but everyone has some powers in their life that influences the life of others: whether it’s how we treat our children, or even just how we speak to the cashier in the supermarket. And as authors we of course have a wider power to influence someone’s life or how the public perceives something through our writing. But although I ask open questions without giving clear answers, because it’s not something you can give a clearcut black-and white answer to for right or wrong, this book was still been met with misunderstanding and resistance by many in the literary field.

Do you think that a work can exist without an author, that when a work is finished it is itself − it begins to live its own life without regard for the author?

I think that it should. If you can’t read a book without knowing something about the author’s life, then that’s limiting. I often find that knowing about the author’s life when reading their work can be very distracting, because you automatically start to compare life and story, and identify certain characters and events in the book, even if it may not be true. I think that for authors who write autofiction, that connection to the author’s real life can be important to understanding their work. But for authors like me, who write actual fiction, the stories growing from the imagination, then any kind of author life identification seriously limits the scope of the literature.

Can a completely amoral author write a great book?

Yes, unfortunately.

Why unfortunately?

Because it would be much easier to not have to deal with the question of whether to read and like a book by an author, who as a person was abhorrent, or had terrible fascist, racist or bigot views. Like for example Celine, or even Knut Hamsun who supported Hitler, but was a superb writer with not a hint of fascism in his literature. The same goes for other art forms, like Michael Jackson, today knowing of his paedophilia does to me make it more difficult to enjoy his music, even if the outstanding quality is the same as before we knew about it. With time though, I think the transgressions matter less, and the art is then what is left. So one has to separate the quality of the art from the character-flaws of the artist. And just hope that somehow, somewhere, the transgressions of the artist are paid for by the artist as a person. That at least makes it easier to fully enjoy the art, I think.

My guru from my adolescence, which continues to this day, the poet Egon Bondy, was completely amoral and a terrible coward who collaborated with the communist secret police, although he considered the communists to be a fascist regime, and as soon as he was alone and took up a pen, he wrote absolutely freely like no other − his poetry, in which he glossed over the world around us, helped us get rid of the disgust in which we grew up, and after all, it was also liberating that a terrifying coward, who made fun of us, helped free us from it …

Bondy is a good example. I don’t know enough about the details of his collaboration to pass any judgement: was he forced or coerced to collaborate, or did he do so willingly to gain favours, or simply being a coward? For colleagues he informed on, I’m sure his actions are unforgiveable. But at the same time, for those his literature helped live through the difficult period, it’s a different and more complex matter.

Knut Hamsun was prosecuted after the war for treason over his open support to Hitler and Nazism. And whether or not this process was fair (there is a lot of discussion and even a film made about it), I feel it frees us as readers, to love his literature despite his very misguided politics.

Yes, art is art because it frees us from what is learned or generally accepted, including, or in the first place, from its author. Your book Kattens tramp, which is about Europe, its history and future, was published at the beginning of the new millennium. Has anything changed since then? How did you see Europe then and how do you see it today?

Wow, that’s a big question. I think five or six years ago I still believed that democracies – and you could say mainstream politics – were very stable in Europe, that the xenophobic, nationalist voices that we heard were just a tiny percentage that didn’t have a chance to reach wider society and become part of the mainstream. And now I think that unfortunately Europe will have to go through a period where the anti-human right will be very dominant. I think that xenophobic nationalism will dominate in most countries before people realize that nationalism leads nowhere, that it’s a dirty blind alley to all-round decline, including that it’s the cradle of every conflict and war, because the basic tenet is always: ‘my country is better than yours’.

What do you think is the cause of the rise of nationalism and xenophobia?

I think the main reason is global capitalism, which has become a global oligarchy, hand in hand with the new technological world, which on the one hand connects people to the whole world, and on the other hand gives the individual less control over what is happening. The world is changing so fast that nobody, but particularly people who live in villages in the countryside, can keep up, let alone find a way to react properly to it. Most people feel they cannot influence anything, so they listen to populist politicians who say: “Before immigrants and refugees, all these foreigners, we had no problems!”

It will be a long process before people realize that the problems that are here − economic inequality has been growing in the last twenty years, with not just the poor but also people from the middle class increasingly being disadvantaged, while a few billionaires are getting richer and richer − are still here. Even when we have nationalistic governments, the problems have not only remained, but have also grown − also without more refugees. Things will only start to change when people understand that the problem is modern unhinged capitalism and deregulated capital flows, which are undermining the democratic system and any attempt at a fair economic distribution, so that the few super-rich can make ever more money without any restrictions.

In my opinion, one of the biggest problems of the above are social, or rather anti-social networks, where technology companies not only do not take responsibility for their business, for which they use public space, but also deliberately use algorithms to distribute xenophobia and hatred in society because people click on negative emotions the most and thus get a lot of money from advertising…

Yes, this is the first time in my life that a system that loves controversial, destructive, brutal thinking and behavior dominates society, because it benefits from this – it earns money based on the number of clicks, which increase exponentially when you write something terrible.

Personally, I think we would have a better world without the Internet, without it at all, despite the benefits it can provide us. There was a brief period when activists, for example, in the Arab Spring, could use social media to spread protests… Between 2010 and 2012, young people in most Arab countries rebelled against tyrannical governments in Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, and so on, encouraging and organizing each other, messaging each other through Facebook and other social media, and holding these huge demonstrations against authoritarian and corrupt governments. They were beaten, but they still used the internet to help each other and organize. But then, those governments figured out how to track down the activists, even their anonymous profiles, and the opposite started happening: instead of the internet helping the pro-democracy movement, authoritarians now used it to suppress it. The internet also became a haven for fraud as well as for all kinds of criminal, depraved and abusive activity.

On the one hand, they are used for police check and on the other hand, for instigating and supporting various dirty tricks, by criminal regimes such as Russia or China, which censor the Internet at home, even with the help of Western companies, while in the West they freely spread their propaganda and disinformation…

Exactly.

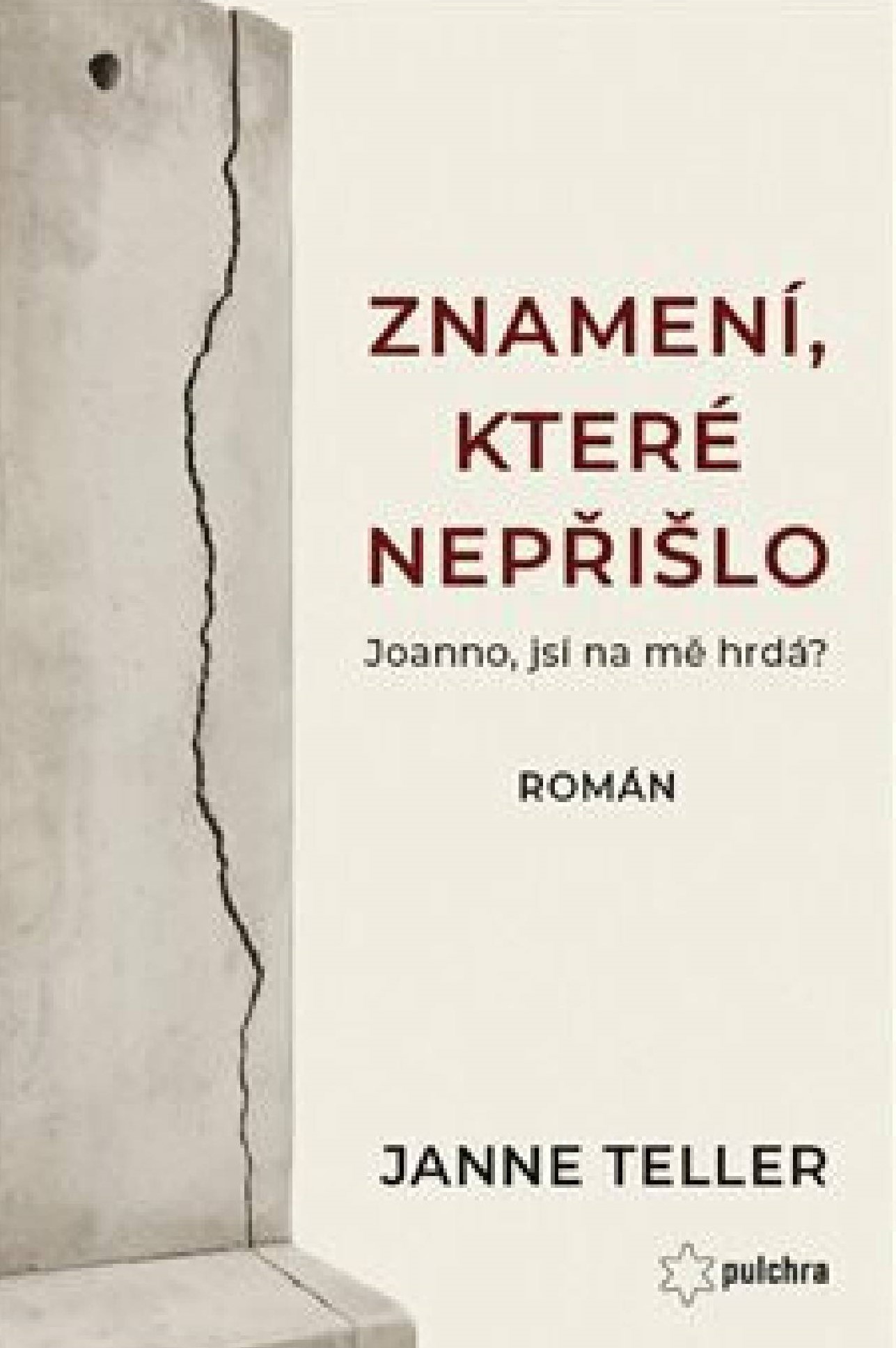

The book ‚The Sign That Didn’t Come’ (‘Are You Proud of Me, Joanna?’) has now been published in translation by Pulchra Publishing House. What sign didn’t come?

The book ‚The Sign That Didn’t Come’ (‘Are You Proud of Me, Joanna?’) has now been published in translation by Pulchra Publishing House. What sign didn’t come?

It is a story about what we do when we encounter deep injustice, how we approach it, how we deal with it or not, how we work with it, take revenge or forgive. And when we cannot achieve justice through the legal system, is it possible to take justice into our own hands?

I ask this question through a high-ranking UN diplomat who lost his daughter when she actively opposed the construction of the wall that Israel is building in the West Bank. At first it seemed like a simple accident, but then he came across some clues that forced him to investigate what really happened to his daughter. He finds the man he believes was responsible for his daughter’s death – he was her lover and also the boss of the human rights organization she worked for. As he can’t bring him to justice legally, he plans to shoot him. A lot happens, so here just to say that I write it to put the reader in the father’s shoes, and ask themselves the question, what would they do if they were him?

What do you think of justice?

Justice is fairness. I don’t think justice is possible always, like when someone has died violently – we can’t bring them back to life, we can only make the situation a little better… In my opinion, the best thing we can get if we can’t get full justice is to find out the truth about what happened. That’s the basis for moving on. That’s also why I think that in the situation that South Africa found itself in after the fall of apartheid, their Truth Commission was so important, where the perpetrators were not held criminally liable if they told the full truth about what happened. I think that if the truth is acknowledged, that’s the best thing we can get – it gives victims as well as perpetrators a kind of guide for their future lives. A true history which helps commit everyone to a better future.

This issue of Babylon magazine will be dedicated, among other things, to Greenland. How did the Danes react to Trump’s remarks about Greenland? How do the Danes themselves perceive Greenland?

The Danes were shocked. We take it for granted that Greenland is part of Denmark. But I also think it woke the Danes up in a way that is not bad at all, because in the past, Denmark did not treat Greenland well – it was a colony where we moved the Inuit into small villages on the coast because it was easier to control them. And while it gave the Inuit access to education and health care, it was an artificial lifestyle for them that caused a number of social problems, including high levels of alcoholism and violence, which is because they are forced to live in a way that is not natural to their culture.

For a long time, Greenlanders have been considered second-class citizens in Denmark. That is why I think some people in Greenland, even some in the government there, are willing to consider whether they should be completely independent, or whether Greenland should be part of America. So suddenly we have a Danish prime minister and a king flying to Greenland to strengthen ties with Greenland, even though it wasn’t a priority for them before.

So I think something good could come out of this Trump wish to take over Greenland, that the Danes would start to treat Greenland and the Greenlanders with much more appreciation, which they should be. A lot of the bad things from the past are still not acknowledged. For example, recently there was a documentary on Danish national television that showed how many resources Denmark extracted from Greenland without Greenland getting any money for it, and the Danes got a lot out of it. But the documentary was taken down. Even if for a few factual mistakes, the reason is I think the simple one that the documentary pointed to something we have not to this day acknowledged, as the Danish nationalists want to hold onto the mythology that Greenland costs the Danes a lot of money.

But due to Trump’s threat, now it’s being discussed in Denmark, how Greenland has been treated throughout history, and still is today. And that’s a very good thing that I believe can lead to a positive change in the relationship between Denmark and Greenland, so it becomes more equal.

And Trump helped make that happen…

Paradoxically yes – unknowingly, he has started this snowball of Danish Greenland-revision that may turn out to becoming a good thing …

If he doesn’t deserve the Nobel Peace Prize… How do you see the monarchy?

I am neither strongly for nor against. In principle, because I believe in democracy, I think I should be a Republican and believe in a republic. But realistically, when we look at different countries and experiences with different systems of government, it seems that monarchies with a hereditary monarch often appear to keep countries calm and stable more than republics with an elected president. The king has one advantage over a president that no one voted for or against him, no one has lobbied for or against him. With a president, there is always a certain percentage of the population that would prefer someone else to be at the head of the country. But the king, who was born to be king, represents the whole country with a unique position to be a unifying symbol for a nation. And in this sense, I think that constitutional monarchies are good if they have only symbolic and no direct powers, and as long as they behave within certain reasonable parameters, also financially. And the relatively modest Danish monarchy is even very popular with few dissenters, compared to for example the lavish British monarchy.

The Danish King not only raises money for charity, but also organizes, for example, the Royal Run, which takes place in major cities throughout Denmark, and he and the entire royal family participate in this run in various parts of the country. Thousands of Danes can say – I ran with the King. This is very different from the elitist British monarchy. The Danes cultivate a „family“ relationship with their monarchy, and it somehow works well like that.

It was a trap: Babylon is a royal revue that promotes the restoration of the Czech Kingdom as a parliamentary monarchy…

So let’s drink to the monarchy for democracy.

Vivat Rex!

Længe leve kongen…

v české versi vyšel rozhovor v tištěném Babylonu 4/XXXIV 15. prosince 2025